The MIT Way

MIT has never had a weakness for the conventional. Founder William Barton Rogers was a bit of an iconoclast himself, and his spirit is very much infused in the customs, philosophies, and mindset of the MIT community. Here, the most mundane tasks are an opportunity for invention. That culture of unfettered innovation has inspired generations of successful inventors and entrepreneurs—arguably more than any other institution on earth.

Mens et manus

“Of all the innovations MIT has produced,” MIT professor Rosalind Williams once observed, “none has been more influential than MIT itself.” Indeed MIT’s distinct model of education has grown generations of prominent doers. It all started with Institute founder William Barton Rodgers and his “New Education,” a philosophy that emphasized the integration of theory and practice. Rogers wanted MIT to focus on practical subjects that tackled hands-on approaches to real-world problems. Laboratory experience, he believed, fused theory and practice more effectively than traditional lectures.

The Institute’s official seal, bearing the slogan Mens et Manus (Mind and Hand), is a perfect pictogram of Rogers’s vision. Adopted in 1864, it portrays a scholar and a blacksmith standing on either side of a stack of volumes labeled “Science and Arts.” Unlike most school mottos, MIT’s Mens et Manus has been a living credo guiding the work of the Institute from Rogers’s day through the present. Nearly one-third of the 2016 National Inventors Hall of Fame inductees hail from MIT.

More

-

Watch a video discussion about the origins of MIT’s motto, Mens et Manus

-

Fred Hargood, Up the Infinite Corridor: MIT and the Technical Imagination (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1993)

-

Merritt Roe Smith, “God Speed the Institute,” Becoming MIT: Moments of Decision, ed. David Kaiser (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2010)

-

Julius A. Stratton, Loretta H. Mannix, Paul E. Gray, Mind and Hand: The Birth of MIT (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2005)

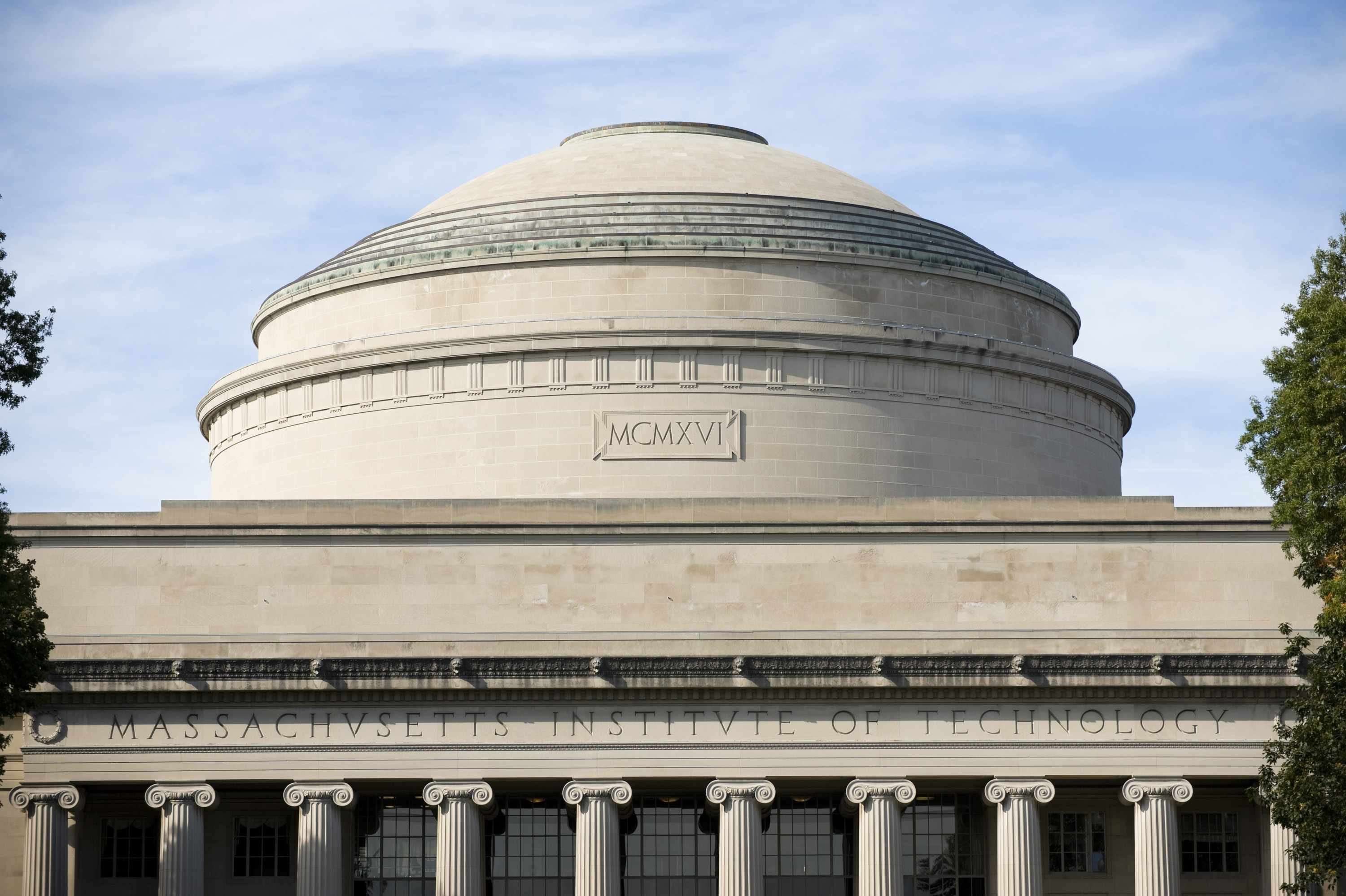

Hacks

The Cambridge campus and its buildings have been, since their inception, an irresistible blank canvas for MIT students’ free-floating ingenuity. Every façade, every hallway, every block of windows presents possibilities and challenges. In 1926, hackers hauled a Ford chassis, with engine intact, up five stories to the East Campus residence hall roof. In 1992, they acknowledged the lofty grandeur of Lobby 7 by outfitting it as a cathedral, complete with organ, faux stained glass windows, and an actual wedding ceremony.

The grid pattern of windows on the 295-foot-tall Green Building has inspired pranksters since its construction in the early 1960s. In 2012, hackers employed the Green Building’s fenestration to create a 21–story fully playable Tetris game. But no architectural feature on campus has inspired more elaborate pranks than the Institute’s iconic “Great Dome.” In 1994, for example, hackers crowned it with a campus police cruiser driven by a dummy occupant hoarding a half-eaten box of donuts. The police cruiser hack is on view at the MIT Museum.

More

-

Institute Historian T. F. Peterson, Nightwork: A History of Hacks and Pranks at MIT (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003)

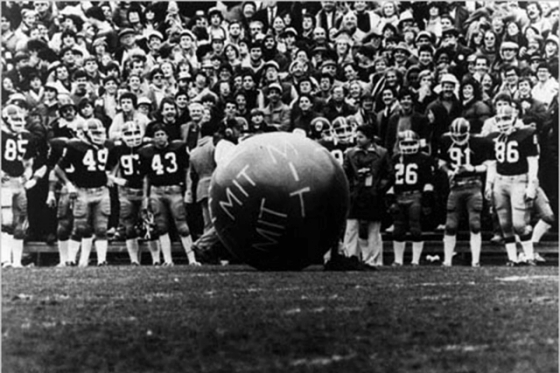

The Harvard-Yale Football Game Hack consisted of a device for inflating a weather balloon, which was buried in the ground near the 50-yard line of the Harvard-Yale game in November 1982 by MIT fraternity Delta Kappa Epsilon. The balloon emerged from the ground and displayed the letters MIT.

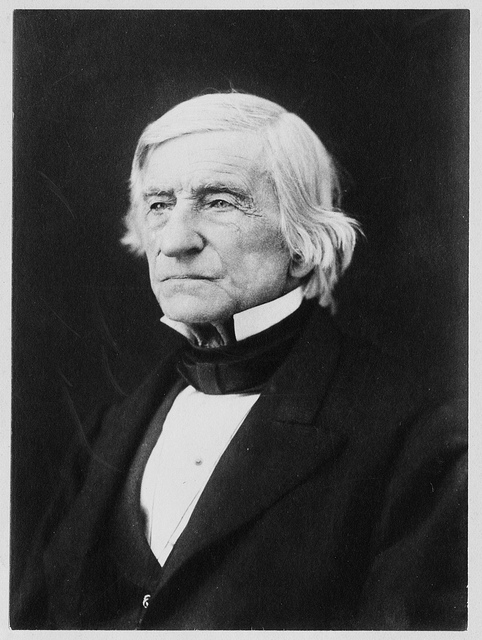

William Barton Rogers

Many of his 19th-century contemporaries at schools like Harvard and Yale considered MIT founder William Barton Rogers a utilitarian. But those who dismissed him as a glorified tinkerer did not know the man. First, William Barton Rogers was not an engineer at all. He was a geologist and nationally recognized authority on mountain ranges (Mount Rogers in Virginia was named for him). He was also a bit of a Renaissance man. A prodigious correspondent, he was comfortable discoursing on literature and philosophy, politics, and world affairs.

While teaching at the University of Virginia (1835–1853), Rogers developed a driving vision about the power of science to raise civilization. He recognized, however, that UVA was not the place to pursue it, for the school was not inclined toward science. In addition, Rogers was a confirmed abolitionist and a Darwinian, and inebriated UVA students had taken to shooting out the windows of professors who displeased them. When Rogers’s brother Henry, seeking a faculty position at Harvard, noted that there was interest in Boston for the establishment of a technical institute, Rogers, who was married to a Bostonian, decided to pursue his dream up north.

More

-

Watch a video discussing attitudes about the manual arts in Rogers’s day

-

Read the Life and Letters of William Barton Rogers, edited by Emma Savage Rogers

-

Fred Hargood, Up the Infinite Corridor: MIT and the Technical Imagination (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1993)

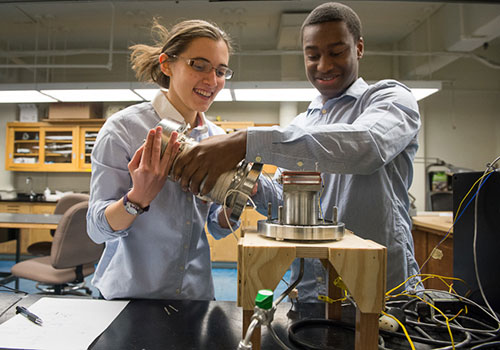

Students have the opportunity to participate in MIT’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP).

Photo: Justin Knight

UROP: The Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program

William Barton Rogers’s dream for a technical institute centered on the idea of hands-on learning. He wanted students to take what they learned in books and put that knowledge to work in the world—and that’s exactly how MIT turned out. In the 1960s, however, Edwin H. Land, inventor of instant photography and cofounder of Polaroid Corporation, believed that MIT could take the hands-on learning approach further. Land, a brilliant amateur scientist who never graduated from college himself, provided the funds to create a program that would encourage and support research-based collaborations between MIT undergraduates and members of the faculty.

MIT Professor Margaret L. A. MacVicar shared Land’s enthusiasm for the idea and in 1969, launched the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program—UROP. The intent was to invite all undergraduates to participate in each phase of research activity as a junior colleague of a faculty member. The student would help write the research proposal, develop a plan, conduct the research, analyze the data, and present the results in oral and written form. Now half a century later, nearly 88 percent of students surveyed recently had participated in UROP during their time at MIT. More than 100 papers are published every year from UROP research.

More

-

Elizabeth Durant, “Faces of UROP,” MIT News (January 8, 2014)

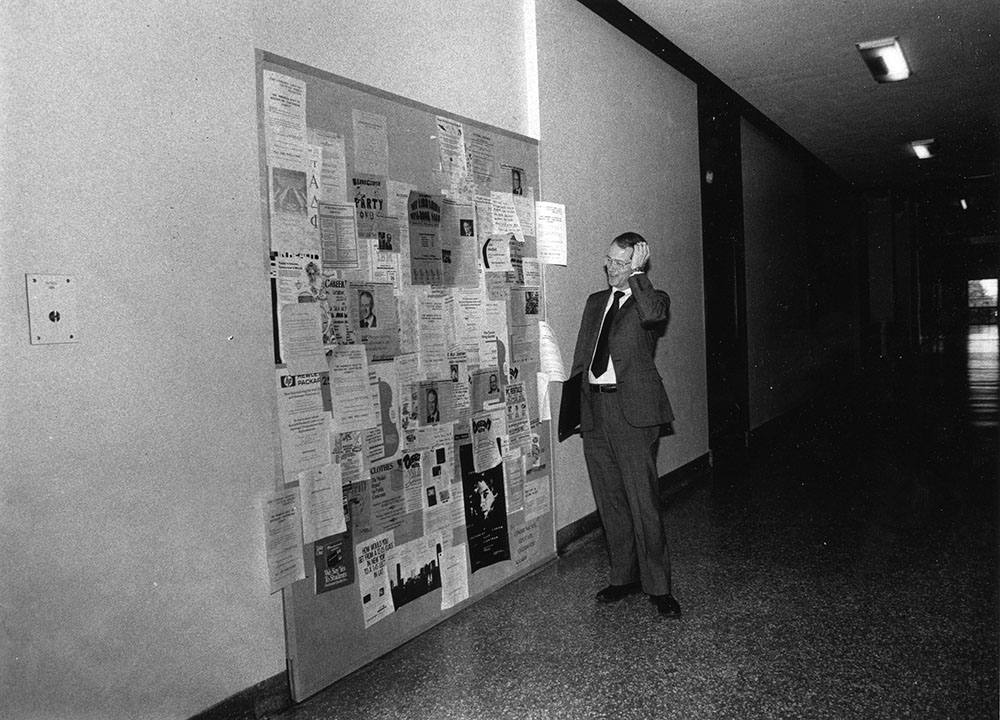

Welcome to MIT! On October 5, 1990, the day that President Charles Vest was to take office, he arrived on the second floor to find that his door had been covered with a bulletin board. Read about the Disappearing President’s Office

Photo: Donna Coveney